|

Yesterday was the World Camera Day and I travelled back in time to reflect on my tryst with cameras.

My first camera was a borrowed one which was lent to me by my cousin who went on to become one of the celebrated cinematographers in the country. That was during my undergraduate medical school years, when prudence in all matters was the overwhelming mantra. More so with photography since one had to save money to buy a 35mm roll and also spend more to print the images later. Each frame was thus precious. I cycled on weekends hugging the camera close, exploring the landscape around JIPMER. Auroville was just being built and the place had a vibrant feel to it. Many unusual structures were coming up including a school with a flowing water body inside, which was aptly called the Last School. All of this provided fodder for my roving eyes. When I was not cycling around, I persuaded my classmates to pose for me in some unusual frames. A few of those photographs received awards in Inte-rmedical Photography Competitions. Life after medical school was a very demanding period as the quest was to enroll in a post graduate course in a good college. I was passionate about psychiatry right from my college days and fortunately got admission in the prestigious National Institute of Mental Health & Neurosciences. Photography receded to the background as I became totally immersed in studies and honing my skills as a psychiatrist. It was only thereafter when I joined the faculty, I could afford a point and shoot camera. This came in handy during my treks with the students. But the lure of photography was kept in check with growing demands of the academic life. I began saving money and bought my first digital camera. No more money spent on film rolls and printing! When the camera arrived, I opened the box like a child eagerly unwrapping a longed for gift! And there it was…a petite camera with a shiny, silvery tinge. I wanted to test it immediately, but the sky was overcast and chances of going outdoors were minimal. I was casually looking around the room and a fork lying on the dining table caught my attention. I was struck by its reflection on the Formica covered table. As I looked closely at the fork and its reflection, it turned into something extraordinary. It wasn’t a simple fork anymore! In its reflection on the shiny, unexceptional surface, it had transformed itself to an object of beauty! I was enthralled to see the extraordinary in a mundane object of everyday life. In that moment there was harmony between the object and its reflection. Henri Cartier-Bresson called it the “decisive moment”: pressing down the shutter button at the right time. Images surround us every moment. We have to see them as if we have never seen them before. The world is full of such moments, if only we open ourselves to them and observe mindfully. There is always a difference between what we look at and what we see. Photography is often about embracing that moment…however fleeting it may be. All too often people spend far too much time preoccupying themselves with the equipment and its technicalities and not enough on just ‘seeing’. If we use our cameras as poetic tools for seeing, and really notice the beauty all around us every day, we will find ourselves astonished by the seemingly ordinary things we might otherwise pass by in our busy, activity-filled lives. The real camera is not in our hands but in the eyes behind the lens of the camera. As I was looking at the fork on the table from a different angle, an entirely new perspective emerged. The fork and its reflection merged together to form a folded hand! It was a visual photo haiku! Photography is a meditative practice for me, providing me with a lens to view life around me. It inspires me to search for beauty in the moment, often right in front of me. At that moment, time slows down and the mind expands in a magical way…

45 Comments

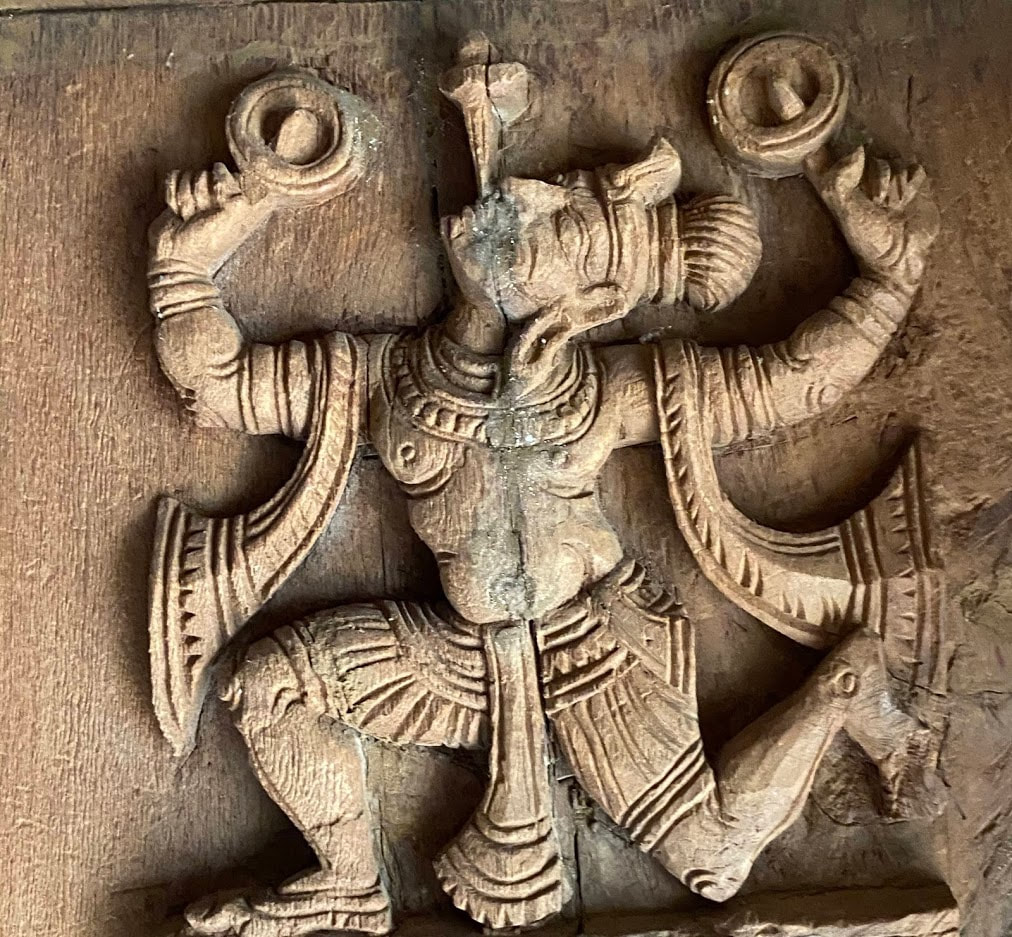

In an earlier posting on the Thiruppudaimaruthur mural paintings, I had briefly mentioned about the wooden carvings. These magnificent creations enhance the beauty of the murals by their presence in that small, confined space. They have been sculpted on the wooden beams that support the ceiling and on the wooden pillars. They are very small in size and include miniature brackets, all exquisitely carved.

The content and depiction of these sculptures cover a wide range of subjects: acrobats, wrestlers, kings and queens, gods and goddesses, ascetics, warriors in battle, and a wide range of animals. The most arresting of them all is the acrobat. He is seen balancing a knife on his face while twirling two circular objects with his fingers. There is a dynamic energy in his body as he executes the task, with one leg firmly placed on the ground and other bent at the knee to maintain the equilibrium. His clothes are swirling in the air during the act. All these aspects are meticulously etched in a small panel of just twelve inches! Such attention to detail is also maintained in the depiction of two wrestlers who are engaged in a bout. It is interesting to see how their limbs are intertwined in the final moment of what is known as a sunset flip in wrestling parlance. There are two hunters, once enticing a bird and the other one hunting down a tiger with a bow. He seems to have just released the arrow which can be seen in the tiger’s mouth! There is a petite Ganesha and also a beautifully carved Lakshmi holding lotuses in her hands. Ascetics and saints follow in various moments: offering pooja, teaching disciples and blessing the king. The ceilings are quite low in each of the tiers supported by horizontal wooden beams. These beams are painted with decorative designs above, and below them are a series of rectangular reliefs, each one of them about 18 inches long and 6 inches high. These contain scenes from everyday lives of that era. The most conspicuous are the battle scenes, which are lively and brimming with energy. Interestingly there are depictions of Portuguese soldiers often shown fighting among themselves, watched over by a local king. Elephants and horses are seen in the battle. The portrayal of a soldier on the arched back of a horse holding the harness tightly yet turning his body to ward off the enemy soldier is quite striking. There is also a delightful and captivating depiction of a woman overseeing a bull fight. In a corner of each tier there are superb life size figures of kings, queens, ascetics, warriors and wrestlers. In addition, there are many small bracket sculptures in the eaves beneath the ceiling. The craftsmanship evident in these sculptures is awe inspiring. It is replete with figures of warriors, hunters, ascetics, dancing girls and musicians. Do have a close look at each of them and marvel at their intricate detailing. The most spectacular of them all is a seated figure of a person with matted hair cascading over his face, sitting on an animal which has the face of a crocodile and the body of a fish. Such forms in Hindu iconography are often referred to as Makara. The term in Sanskrit means “sea dragon” or “water monster”, a mythical animal with the body of a fish and the head and jaws resembling a crocodile. The head is sometimes also depicted as an elephant. The person seated on it could be Varuna since he is reportedly the only person who can control it. Is Makara a mythical animal or a real one that existed eons ago? Intriguingly some have suggested that Makara bears a striking resemblance to the approximately 155 million year old Pliosaur fossil. Pilosaur existed during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods during which time it was one of the top predators of the oceans. If this were to be true, how did the authors of Bhagavatam, Ramayana and Mahabharatha where Makara is mentioned, get their information?! Beyond all these speculations, the sheer artistry of depiction is stupendous! There is a wide array of animal figures deftly sculpted. Noticeable among them are beautifully carved elephants, bulls with stunning humps, ferocious tigers with prey in their mouth, intertwined snakes, doe eyed deer, galloping horses, plump rabbits, hulking camels and gorgeous hamsas. The hamsa being a “noble bird par excellence” is a favorite decorative form in Indian art. In Hindu religion it is taken to be the vehicle of Brahma and the goddess Saraswati and is considered to be superior to other birds owing to its graceful gait, swift movement and virtuous quality. In its ability to separate milk from water, it is also considered as a symbol of the discriminating mind. Temples, though they are the gateway to the other world, are deeply rooted in the world around us and hence it is not surprising to find animals sculpted within their precincts. The depiction of animals and birds ranges across a wide spectrum in Indian arts. They have always been a perennial source of inspiration to artists to create multiple forms, motifs and designs in decorative arts. Animals are sculpted in their natural forms, as well as divine symbols. Hindu mythology lays enormous significance on the metaphoric significance of animals. For example, snakes figure prominently in the Hindu pantheon: Vishnu slept on it, Krishna danced on it and Shiva wears it around his neck! Hence it is not surprising that animals figure prominently in temple architecture. They assume a spiritual quality as they also serve as vahanas for the god and goddesses. Animals are also depicted as composite forms in very imaginative ways in sculptures. The composite animals are a combination of the natural and the supernatural, of animal and the divine. Composite sculptures reflect the imagination of the artist and convey a deeper meaning. They are not mere physical forms: they symbolize a thought or an idea. The term Vyala is applied to such imaginative creatures and they can be noticed as decorative motifs in all temples. The kaleidoscopic variety of wooden sculptures in that small, confined space reflects the ingenuity and creative imagination of the artists. Though frozen in time, they seemed to come alive as I gazed upon them. I was wondering whether the people in the murals and the sculpted figures were looking back at me as I was looking at them! My entire experience in the dark cloisters of the gopuram at Thiruppudaimaruthur was akin to that of Alice in Wonderland. Instead of going down a rabbit hole, I ascended the dark steps to discover a magical realm, found myself in a fantastical world like her and ended up “curiouser and curiouser”! It was an endless reverie In a magical realm Of unbridled creativity As I bid adieu I offer you a seat To sail along with me To savor its wonders.. Glimpses At: photos.app.goo.gl/EshvHrQvNmfNEkov6 Kindly do not share the album without informing me! And feel free to post your comments here!! As my previous posts would have indicated, I am besotted with murals. When I read that there are murals of the Nayak period in Tirunelveli district, I was keen to have a glimpse of them. When I researched a bit more, I realized that they were rather difficult to view and would require oodles of clearances. It dampened my spirits initially. As providence would have it, within the course of a few weeks, people who could help me through it got in touch with me. It is through their unstinted help and guidance that I was able to get access to many temples in the area. I am deeply indebted to their spontaneous assistance.

Let me start this journey with an account of our visit to Thiruppudaimaruthur. Sri Narambunathaswamy temple at Thiruppdaimaruthur in Papakudi Taluk, is one of the oldest temples in the region. It is situated in a picturesque location at the confluence of the Gadana and Thamirabarani rivers. It was built in 650 BCE by King Maravarman. The presiding deity is Lord Shiva. The Shivalinga is said to have been discovered when Veera Marthanda Pandy was hunting a deer. He found the deer hiding at the foot of tree and decided to cut it with a sickle. doing so, to his great shock and surprise he found a Shiva Lingam. To atone for his act, he built the temple and to this day the lingam is seen with a cut on the head. Because of this, abhishekam is not offered to it. The lingam is tilted to the side and there is another interesting anecdote to explain it. Karuvur Siddhar, one of the most renowned ascetics, wanted to have a darshan of the lord. But when he reached the place, there were flash floods in the Tamirabharani and he was unable to cross the river. Moved by his prayers, an invisible voice guided him to cross the river which parted to allow him to reach the temple. Since the Lord was leaning to listen to the prayers of his devotee, the lingam is seen tilted to the side! It was a pleasant journey to the temple from Tirunelveli through verdant green fields. I was keen to reach it early to have a glimpse of the murals before sunset. To our great disappointment we found that there was no one at the temple. We went around its deserted precincts, fervently hoping that someone would turn up soon. To our great relief the person responsible to permit us entry came in shortly after. He opened the iron gates of the main gopuram and we started ascending the steep steps inside in sheer darkness. It was quite an effort to scale the high, narrow steps and when I reached the first tier of the gopuram I was totally unprepared for what I saw. Every inch of the wall was covered with exquisite paintings, the likes of which I had never set my eyes upon. As it was quite dark inside, it was quite a difficult task to have a good look at them, which we accomplished with the lights from our mobile phones! The paintings are in the five levels of the gopuram. Each level has a cruciform outlay which is bisected by exquisitely carved wooden pillars (more of it in a later post!). The carved pillars and painted ceilings create a perfect sense of rhythm. Four of the five floors in the gopuram consist of hundreds of murals portraying various religious themes and places of worship while the murals on the second floor are narratives depicting scenes from daily life illustrating the culture and socio-economic life of every part of the society, from the king to the common man in addition to battle, in an almost photographic mode. In an extraordinarily lively manner they offer us tantalizing glimpses of the era. In each panel there is a continuous depiction of various scenes with stylized borders of flowers, decorative motifs and animals. Each one of them requires a detailed account. Some of the exquisite ones include a dancing Siva, Vishnu as Seshasayi, a seated Ganesha, marriage scenes of Siva and Parvathi and episodes from Ramayana. Another spectacular painting, two metres tall and 3.6 metres wide, portrays a sail-ship with Arab traders bringing horses. Cavalry formed an important wing of the army and thousand of horses were imported. One can see these horses in action in the battle scenes. Perhaps the most vivid ones are the battle scenes, which are replete with dynamic energy. They portray warriors on horses and elephants, fighting each other with spears and sword. One can see sepoys with long topees and men holding flags, blowing trumpets and playing drums. These paintings have baffled art historians for several decades and they have debated on what was the war fought and who the adversaries were. There is a suggestion that these murals portray the Tamirabarani battle in 1532 between the King of Travancore, Bhoothala Veera Udaya Marthanda Varma and the Emperor of Vijayanagara, Achyutadeva Raya. As per records, the battle was at Aralvaimozhi Pass, near Thovalai in Kanyakumari district. The war erupted when the king of Travancore Udaya Marthanda Varma after refusing to pay obeiscence to Achyutadeva Raya, annexed much of the territory of the Tenkasi Pandya ruler Jatila Varman Sri Vallabhan, who in turn approached the Vijayanagar emperor for help. To teach them a lesson the emperor himself undertook a 'Dhikvijayam' with his enormous army. The joint armies were defeated by Vijayanagar army and Marthanda Varma and was produced before Achyutadeva Raya at Srirangam who pardoned him after a light punishment. These paintings date from second half of 17th century and bear resemblance to those at Lepakshi which I had described in an earlier post. The style is characterized by sharp angularity of the figures with elongated hands, fingers and feet. Deities are usually shown frontally whereas the rest are depicted in profile. Great care is taken in the depiction of different costumes and textiles with very captivating designs. The colour palette is quite varied with a judicious mixture of green, red and black. Interestingly a few of them have a sepia tone as one would see in period photographs. I also wondered as to why these murals have been painted inside the gopuram (like the Chola murals in Brihadeeswar temple at Thanjavur) and not in the pradakhina passage around the sanctum where devotees would have greater chance to see them. Yet at the same time, safely ensconced inside the dark interiors of the gopuram, they have withstood the travails of time well. The paintings do not bear the names of the artists. Given the extent of the work, several artists must have worked in unison to create these magnificent paintings. What sets these paintings apart is great thematic diversity, boldness in depiction and brightness of a rich palette of colors. These unknown artists are also magnificent storytellers! They have succeeded in creating an enchanting, enlivened space. As I walked through the five tiers, absorbing the myriad paintings, I was transported in time and space. It was a transformational experience. To a large extent the history of painting in South Asia has focused on earlier works such as the murals at Ajanta and the North Indian courtly paintings of the Rajasthan and the Mughal empires. Though the Chola murals have attracted some attention, the paintings of Nayak period have been relegated to the background. With my own personal involvement and passion in visual arts, I keep wondering as to what draws me to artistic creations like these. What is their mysterious pull? Is it just the attributes of the artworks itself or the way it resonates within me? Perhaps artworks are intertwined with our personal interests, predispositions and a larger world view. Something that is often referred to as ‘rasanubhava’: a delicate interplay between the observer and a work of art. Such moments often encompass within it a sense of intimacy, belonging and intense closeness with works of art which I continue to experience in many a place I visit, like this one. The dusk was settling in and it was time to leave the company of these treasures. As I descended the steep steps, with much reluctance, after one and a half hours, these words of Kandinsky resonated deeply within “Color directly influences the soul. Color is the keyboard, the eyes are the hammers and the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the hand that plays, touching one key or another purposively, to cause vibrations in the soul.” As I wander among These paintings from the past In flickering light I find myself pulled inside Their colorized world Where paintings meet poetry… Savor these painting…slowly…and there are scores of them at: photos.app.goo.gl/JinMXUCTkji1Yz8P6 It was indeed quite difficult to photograph them in darkness and I was keen to avoid using the flash from my regular camera. Two of my friends who accompanied me were kind enough to shine light from their mobile phones for me to have a glimpse so that I could photograph them with my iPhone! Look forward to your comments here…and not in google photos! |

Dr Raguram

Someone who keeps exploring beyond the boundaries of everyday life to savor and share those unforgettable moments.... Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed