|

As I was walking in the garden I could feel the crunch and quiver of the leaves underfoot. Some were scampering in the wind like children at play. My attention was drawn to a single leaf which was glowing under a haze of sunlight. I was awed by its limpid beauty and luminous physicality. Though shriveled and withered, it seemed to hold onto memories it treasured in its collapsed yet vibrant veins.

The dropping of leaves by a plant is called abscission. It is a natural order of progression during the life cycle of most plants. In the process of leaf abscission, plants periodically shed their leaves. Leaf abscission involves a number of biochemical and physical changes. The chlorophyll begins to break down, revealing other colours like oranges and yellows that were always present in the leaf, but which were masked by an abundance of the green pigment. The fallen leaves dry, yet retaining their colours. Though wilted, the leaf was elegant in its innate beauty. As I was looking at it, I was reminded of Wabi-Sabi, an ancient aesthetic philosophical concept in Zen Buddhism. It is rather difficult to translate the term in English. Wabi roughly means ‘the elegant beauty of humble simplicity’, and Sabi refers to ‘the passing of time and subsequent deterioration’. It urges one to find beauty in every aspect of imperfection while acknowledging its impermanence in nature. It draws attention to three simple realities: nothing lasts, nothing is finished, and nothing is perfect. Recognition of these aspects facilitates a more connected way of living not just with nature but also within our inner selves. Awareness of the impermanent nature of phenomena helps us to adopt a more reflective stance to our attachments and enables us to prepare for separation and loss that is inevitable. It is also reflective of the Buddhist concept of Anicca - that all existence is temporary - which is evocatively articulated in the Mahaparinibbana-sutta (Discourse on the Final Nirvana), which describes Buddha’s last days and his passage into parinibbana. Aniccaa vata sa"nkhaaraa — uppaada vaya dhammino Uppajjitvaa nirujjhanti — tesa.m vuupasamo sukho. Impermanence pervades all things, They arise and cease, that is their nature: They come into being and pass away, Release from them is bliss supreme. The dry leaf on the ground, with nothing to anchor it, seemed lost in its own world, drifting in the wind. Where was it heading to? Shelley sought the answer in his “Ode to the West Wind”, a poem that was written in the woods as he was observing the multicolored dried leaves buffeted by the wind. Drive my dead thoughts over the universe Like withered leaves to quicken a new birth! And, by the incantation of this verse, Scatter, as from an unextinguished hearth Ashes and sparks, my words among mankind! Be through my lips to unawakened Earth The poem was written under strained emotional circumstances and reflects Shelley’s quest for renewal. Four months before Shelley began writing it, his son William had died; the year before, he had lost his daughter Clara and he himself was plagued by ill health and creditors. In addition to his personal woes, the public had been largely indifferent to or critical of his writings. The poet asks the wind to scatter his writings across the earth in hope of inspiring new thoughts and works. The play on the words “leaves” is interesting as they are found both in trees as well as in books! The wind is an important part of nature’s regenerative cycle. The leaf is bound to fall from the tree one day, but doesn’t ‘pass away’, it ‘passes on’. It aligned with forces of nature while it was attached to the tree. Its journey continues even after it falls down onto the earth albeit in a different form. It will soon be digested by various actors on the ground: worms, insects and birds till all that will remain are its skeleton which will be absorbed deeper into the earth. When the leaf returns to its original oneness with the earth, it resumes its own nature. In death it will leave more nutrients in the soil than it ever consumed during its lifetime. Every leaf teaches us something about life. We are leaves ourselves. At some time we too will be separated from the tree of life and meander in life like this little leaf. We have had our seasons of flourishing and inevitably over a course of time, we are back to our bare bones. Nothing ever stays exactly the same and nothing is ever repeated in exactly the same way again. This was wonderfully expressed by the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus some 2,500 years ago, who remarked, “Everything flows, nothing stands still…nothing endures but change.” Our life is like a dance on the Mobius strip. The Mobius strip is a surface with only one side and one boundary. As we trace our finger on what seems to be the outside, we find ourselves suddenly on what seems to be the inside. If we continue, we will find ourselves back on what seemed to be the outside. If life is a Mobius strip, whatever is inside us merges with what is outside and vice versa and both influence each other. In that exchange we co-create what we call reality. In so doing we return to the wholeness, the natural state, in which we were born. Whitman is said it perceptively, “All goes onward and outward, nothing collapses” Leaves remind us that to truly live, we must face and embrace impermanence and change as a natural part of life, in our own inner garden. Impermanence is the beauty and the energy of life. The wilted leaf Glows with inner light Merging with the earth Harmoniously From non being To being… Look Forward To Your Comments & Reflections On This Post.....Here!!

86 Comments

In all my sojourns to heritage structures, including temples, I am drawn into the aesthetics of the place.

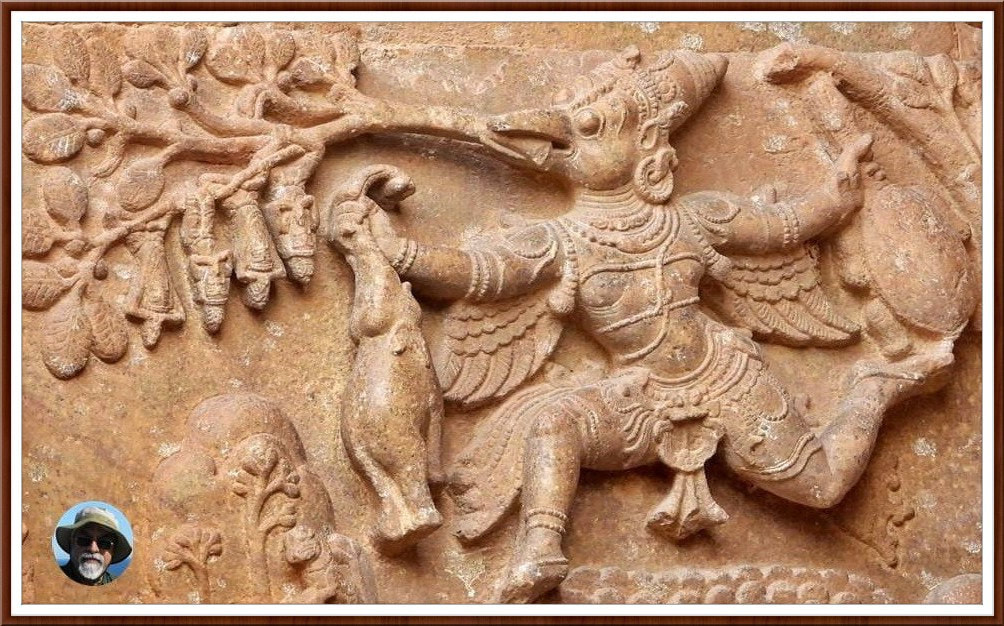

The temple at Thirukurungudi in Tirunelveli district is one such magical space. It is a rich repository of hundreds of outstanding sculptures about which I will be writing in detail sometime! The temple tower is studded with beautifully sculpted panels, each of them just two or three feet in size. As I was observing them, this particular panel attracted my attention. It was an unusual depiction of Garuda. On this Garuda Panchami day, let us dwell a bit more on the story behind this exquisite panel. The story goes like this… Garuda's father was the Rishi Kashyapa. He had two wives, Vinata and Kadru, who were daughters of Dakhya Prajapati. (Incidentally, there is small, beautiful temple dedicated to him in Odisha). Kashyapa, on the pleadings of his wives, granted them their wishes; Vinata wished for two sons and Kadru wished for a thousand snakes as her sons. Both laid eggs. While the thousand eggs of Kadru hatched early, the hatching of the two eggs of Vinata did not take place for a long time. In due course, when the second egg hatched, a fully grown, mighty bird form emerged as Garuda. Unfortunately, one day, Vinata entered into and lost a foolish bet (that’s another story!), as a result of which she became enslaved to her sister. Garuda went in search of the nectar of immortality to free his mother from enslavement and while on his way, saw his father, Sage Kashyapa, deep in meditation. He came down to earth and bowed his hands to his father in greeting. This was the first meeting between the father and the son. Garuda explained to him that he was on his way to obtain the nectar of immortality to save his mother. Kashyapa blessed his son and told him that there was a lake inhabited by an elephant and a tortoise. Though they were brothers in their previous birth, now they were each other’s deadliest enemy and were constantly at war. He advised Garuda to eat both of them to get the nectar. With his father Kashyap’s blessings, Garuda flew to the lake. He saw the elephant and the tortoise and seized them with his giant talons and flew into the sky. He was seeking a place to rest and eat his food and saw a place surrounded by beautiful, tall trees. When the trees noticed a huge bird-like creature flying overhead, they started trembling in fear. They thought that it would definitely crush them under its weight. When Garuda saw them getting frightened, he flew off in another direction. Just then, a huge banyan tree saw him and called out, “Garuda, come and sit on me. My branches are quite strong, they will surely support you. Come, rest and eat your food.”Garuda then flew to the tree and sat on the branch. The moment he sat, the branch broke off and began falling down. As the branch was dropping, Garuda observed to his great amazement, that some sages were hanging upside down on the branch. He realized that if the branch fell, they would surely die and immediately grabbed the branch with its beak. The sages who were in deep meditation were Valikhyas, a group of thumb sized divine sages with great ascetic powers. The panel depicts this particular scene in great detail. One can notice Garuda in the act of flying with the branch in its beak and the sages in the act of penance. While one foot is gripping the elephant firmly, the other is holding onto the tortoise. The detailing of the ornaments and the wings is quite exquisite. The energy and dynamism in such a small panel is a tribute to the skills of the unknown sculptor. |

Dr Raguram

Someone who keeps exploring beyond the boundaries of everyday life to savor and share those unforgettable moments.... Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed