|

I am besotted with gardens. When I walk through a garden I am enveloped in a symphony of colors, rustling leaves, bird and insect sounds wafting through the air. It is an immersive experience imbued with a sense of tranquillity. As Bacon commented, “it is the purest of human pleasure.” Gardens are often seen as a refuge, a place to forget the "real" life that lies outside. But they are also quintessential healing spaces.

Oliver Sacks, the famed neurologist and author, whose birthday falls today, wrote a small, wonderful essay “Why We Need Gardens,” in his book “Everything in Its Place: First Loves and Last Tales,” which was published posthumously. Since his place of work was just across the road from the New York Botanical Garden, he noticed how patients who were unable to function inside a hospital setting seemed to come alive in the garden. An elderly lady with Parkinson’s disease, often frozen, unable to initiate movement was more mobile in the garden and even climbed the rocks up and down many times, unattended. Patients with very advanced dementia who had difficulty in even tying their shoe laces, when put in front of a flower bed with some seedlings knew exactly what to do. He described such deep bonds people have with gardens as “hortophilia.” In his words, “I cannot say exactly how nature exerts its calming and organizing effects on our brains, but I have seen in my patients the restorative and healing powers of nature and gardens, even for those who are deeply disabled neurologically. In many cases, gardens and nature are more powerful than any medication”. He went on to add, “In forty years of medical practice, I have found only two types of non-pharmaceutical ‘therapy’ to be vitally important for patients with chronic neurological diseases: music and gardens.” Gardens saturate our awareness and the boundary between our self and the world fuses and we feel more alive and flourish in that moment. It leaves a lasting trace in the innards of our minds. For Thich Nhat Hanh, garden was a metaphor for the mind. He wrote, “First, you have to take care of your own garden and master the art of gardening. In each one of us there are flowers and there is also garbage. The garbage is the anger, fear, discrimination, and jealousy within us. If you water the garbage, you will strengthen the negative seeds. If you water the flowers of compassion, understanding, and love, you will strengthen the positive seeds. What you grow is up to you.”

0 Comments

Aphorisms have been around for long and are iconic “short, pithy sentences” which convey an important observation in a concise manner. By sheer chance I came across a slim book, ‘The Zürau Aphorisms’, written by Franz Kafka. He wrote these aphorisms while recovering from tuberculosis and contemplating the end of his life. In it, he touched on a number of topics: religion, women, marriage, guilt, family and afterlife.

When they were originally published after Kafka’s death in 1924, the contents were not ordered correctly. One day, the Italian critic Roberto Calasso found Kafka’s original notes in a folder at Oxford’s Bodleian Library and he restored Kafka’s wording from these notebooks. He ensured that the layout was as Kafka had designed: each aphorism sits alone on the page, surrounding by a swathe of white space. The book offers an intimate glimpse into Kafka’s thought process. One of the aphorisms in the book that caught my attention was the short and pithy, “A Cage Went In Search Of A Bird.’ It intrigued me. What did Kafka mean when he wrote it? The internet is replete with hundreds of interpretations of this aphorism. I kept reflecting about it and to me the metaphor of cage is representative of our personal and professional frameworks that influence and impact our lives. We weave our lives around them and build cognitive enclosures, which often become rigid over time. Though they offer a sense of security, yet at some point, we cast our gaze outside these structured confines and spy a bird which symbolizes values such as exploration, lightness of being, and freedom. It inspires us to pry open our mental constraints and go in search of it. In that pursuit our cages grow wings and we soar. It is a transcendental search, in which each moment whispers the eternal truth. As Rumi observed “What You Seek Is Seeking You.” What would be your way of reflecting on this aphorism? (Penned on Franz Kafka’s Birthday!) On the occasion of the World Parrot Day (on 31st May), let me share a story by Rumi, ‘The Merchant and the Parrot - Daftar-e-Awwal - (Masnavi Book 1: 18)’.

A lovely parrot was presented to a Persian businessman by his Indian trading partners many years ago. He kept the parrot in a secure cage where he could keep an eye on her and listen to her sweet song every day when he came home from work. When the time came for him to go to India on a business trip, he asked his family to choose what they wanted him to bring back as gifts for them. Each one, including the little green parrot, requested something dear to his or her heart. My beloved master, she said, my heart truly wishes nothing from my motherland. However, if you happen to come across a bunch of parrots like myself, please offer my greetings and inform them that I'm stuck in a cage in Persia and miss them very much. Ask them if they believe it's fair that they can fly around the country while their cousin languishes in captivity. I beg you to contact them on my behalf and seek their opinion on how to assess my position. The merchant vowed to track down the birds and relay her message just as she had expressed it. When he arrived in India, one day, he came upon a flock of parrots chirping loudly in a forest and faithfully conveyed his parrot's message. Before he could finish, one of the parrots began to shiver uncontrollably, tumbled of the tree and appeared to be dead. He became disturbed, feeling a deep sense of sorrow that he'd unnecessarily killed the unfortunate bird. When he arrived back home, he handed out the gifts that each person had requested, but he didn't say anything to his parrot. The bird, who had been waiting for her mates' responses with bated breath, finally couldn't take it any longer and asked the merchant, “So, where's my gift? Tell me about the Indian parrots. What did you see and hear from them?” The merchant responded hesitantly, “I relayed your story to a flock of parrots in the woods. However, before I could finish, one of them began to tremble and suddenly fell from the tree, dead. I'll never be able to forgive myself for killing the poor bird”. On hearing this, the parrot fell on the cage floor, motionless. The merchant couldn't believe what he was seeing and he felt guilty for causing yet another death. After some time, the merchant nervously unlocked the cage door and carefully lifted up the bird, carrying her to the garden, resting her on the ground while he dug a grave for her to be buried. To his great surprise he saw the parrot flying up to the nearest tree, sitting on a high branch, blissfully staring at her former master. The merchant was taken aback, “I'm overjoyed to see you're still alive and well, but tell me, what did I say that made you want to imitate the bird in India? Now that you're free, tell me your secret”. That parrot taught me how to free myself said the parrot, “Without saying anything, he let me understand that my confinement was due to my lovely song, my ability to amuse you and your visitors. My priceless voice was, in fact, the source of my enslavement. He taught me that my liberation would be found in the act of dying”. After saying this the parrot said her final goodbyes to her master and flew away. The beauty of this story is that it can be read at different levels. It is about the limits of love, how loving someone can also mean letting the person go. At another level, the parrot here symbolises the human soul, trapped in the cage of the body. It is a symbol of our inner reality: the bird of our soul aspires to fly away from the material cage of worldly life. Rumi urges us to disentangle ourselves from the worldly life, open the cages of material life and let our souls ascend to a larger reality. The motto for the World Parrot Day this year is, “ Be smart and creative, be more Parrot”! ( Do pen your thoughts in the blog…whenever you want to listen to the parrot!) There is magic in nature everyday. Decades ago, after finishing my lecture in a professional meet, I ventured into Mulki, a hidden gem nestled in the coastal region of Karnataka, in the company of the hugely talented birder, Ramit Singal. It was a bit chilly in the morning and as I scanned the landscape I had the first glimpse of the Eurasian Curlew. It was standing at the edge of the water on its stilt-like legs, probing the ground with its long, curved bill. It was absorbing to watch its slow, rhythmic movements as it sauntered across the land, in search of food. Though at first sight it looked ungainly, there was an unmistakable aura of majesty in the bird.

There is a curious tale of the curlew and a Christian saint, Beuno. According to legend, St Beuno, a 7th century Welsh abbot was on a journey from the Lleyn Peninsula to Anglesey. The small boat that he was travelling in, was suddenly rocked by a gust of wind and his book of sermons dropped into the sea. St Beuno was distraught as he watched it sink. It was at this point that a miracle happened. A brown bird with a long, downward curving bill wheeled out from the shore and swooped down to the water, picked up the book and returned it to the shore to dry on the rocks. Overcome with gratitude, St Beuno blessed the curlew and decreed that from that moment on, curlew nests would always be difficult to find and should be protected for ever. Indeed curlew nests are notoriously difficult to spot! 21st April, which is the feast day of Saint Beuno, the patron saint of curlews, is also celebrated as World Curlew Day. Curlews have complex pitch variations and harmonics that are often described as haunting, but can also be ecstatic. Robert Burns wrote, ‘I never heard the solitary whistle of curlew on a summer noon without feeling an elevation of soul, like the enthusiasm of devotion or poetry.’ At night, however, the same sound was believed to emanate from the dreaded Seven Whistlers. In both Welsh and English mythology, these birds of doom fly across the night sky, and to hear them is to be warned of death. But, as the traditional Welsh ballad ‘The Curlew’ mentions, they combine both joy and despair : “Your call is heard at high noon-day A wistful flute across the mere, As herdsman’s whistle far away. Your call is heard at midnight clear then hear we, as you swell your keen, Barking afar, your hounds unseen.” Mary Colwell wrote a memorable book, ‘Curlew Moon’ documenting her 500 mile journey across varied landscapes of the UK, observing and documenting the curlews. The first World Curlew Day in 2017 was her brain-child to shine a light on the plight of this unique bird. There is sheer beauty in the avian kingdom. Every time I observe a bird like the curlew it widens my perspective, and I immerse myself in the sounds, colours and patterns that I was not aware of before. It opens the door to an endless repository of wonder. “As I watch The bird spreads its wings Soars across the sky Leaving its footprints In my memory” The Curlew would love to know what you think of it and do pen your thoughts here! I have an abiding interest in monuments and heritage structures. One can find an interesting ancient structure in every corner of our country.

On this International Day of Monuments and Sites, let me draw attention to the first site I visited two decades ago. It was an eye opener for me as I was totally awestruck that such beautiful structures can be built of mud. The terracotta temples at Bishnupur, West Bengal are a marvel. I had seen pictures of the terracotta warriors of China, but to find an entire complex of temples built with clay was a revelation. Built by the Malla kings between 10th and 17th centuries, these temples are dedicated to Vishu and hence the name Bishnupur. The unavailability of stone in the region probably led to the use of terracotta in building these structures. Often paucity of traditional building materials energizes the artisans to explore new mediums and the temples of Bishnupur are an enduring testimony to their innovative spirit and skills. Ahalya and myself spent an entire day visiting all the monuments. Since they are made of earth, vagaries of weather have taken a toll on many of them. But the ones that remain well preserved are a treasure to behold. The attached photo is that of Shyam Rai temple. It is the most profusely carved temple in Bishnupur. It has one main shikara on top with four on all sides and hence referred to as the Pancharatha temple. The intricate floral motifs and delicately carved scenes from the Puranas come alive as the rays of sun gently caress them. I couldn’t take my eyes off the enchanting ‘Rasamandala’, portraying Radha and Krishna surrounded by the gopis, linking their arms to form a circle . We spent several hours visiting other temples, each one distinctly beautiful. Terracotta temples are not unique to Bishnupur and there are several others in many parts of West Bengal. The temples at Bishnupur stand apart in terms of their exquisite, intricate work in terracotta. It is not just these creations in clay that set Bishnupur apart. There are a host of interesting repositories interwoven into the cultural landscape of the region. Foremost among them are the Baluchari saris.One of the unique features of these saris is that they tell stories, from the Indian epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Unlike the Banarasi saris, the Baluchari does not include zari work, and instead relies exclusively on the silk thread-work for effect. We were keen to see how they are actually made and visited a weaver. He was working on a big loom in a dark, subterranean space with only a small lamp as the source of light. Weaving a Baluchari saree is a time intensive, laborious process. The designs are first sketched and then copied on to punching cards which are used in the Jacquard loom to weave the pattern. The cards have punched holes which correspond to the design. Thousands of punched cards are required for one design. It takes almost 4-6 weeks to weave a single sari. When we had a glimpse at some of the finished products, we were wonderstruck at the stunning details and the sheer artistry. Another distinctive craft of Bishnupur are the Dashavatar cards. All the ten avatars of Lord Vishnu are drawn on these cards. The ‘Dashavatar card game’ is reportedly a highly complicated one, with numerous rules and regulations, played using 120 cards by five people. They are much like the Ganjifa cards of the Mysore region. Can music be far behind? Bishnupur Gharana is a Dhrupad style of music. It flourished among the musicians of the region and is known to have influenced many of the songs composed by Rabindra Nath Tagore. As we were leaving after an absorbing day, when I looked back, the temples were glowing in the last rays of the setting sun, an image that is deeply imprinted in my mind’s eye. Bishnupur is a repository of a rich cultural heritage which is not confined to the beautiful monuments alone, but also finds expression in various textiles and crafts. It is imperative to protect, conserve and reconnect with them and tune our ears into their timeless stories. Do pen your thoughts/reflections here! As we advance in life, we all wither at some time either due to illness or merely because of the process of ageing, facing the unavoidable terminality of life. In its throes should we, “rage, rage against the dying of the light” or open the cage for the bird that we nursed so long and let it go? It is a delicate dance.This dilemma is the core premise in O’Henry’s story ‘The Last Leaf’.

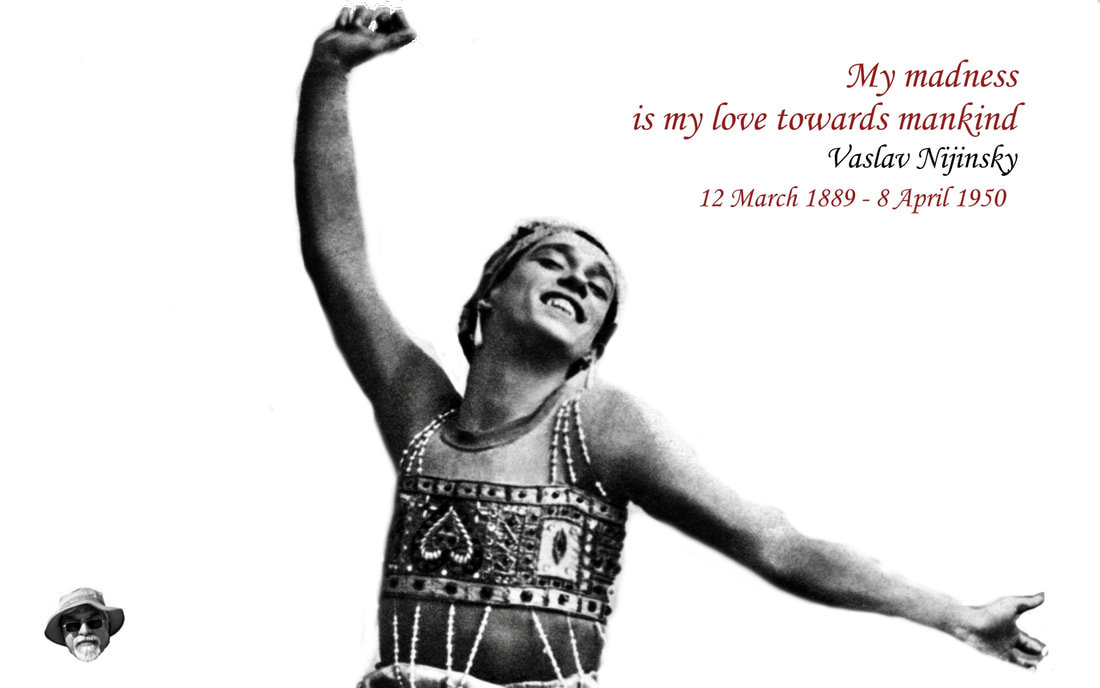

In the story, two young artists named Sue and Johnsy live together in a small apartment in Greenwich Village struggling to make ends meet. As winter approaches, their dreams of becoming successful artists seem to be fading. However, their lives take an unexpected turn when Johnsy falls ill with pneumonia and becomes convinced that she will die when the last leaf on the tree outside their window falls. Sue, being the practical and optimistic one, tries to reassure Johnsy that she will recover and that the last leaf will not fall until she is better. Despite Sue's efforts to lift Johnsy's spirits, the harsh winter weather and Johnsy's worsening condition only strengthens her conviction that the end is near. In desperation, Sue reaches out to their elderly neighbour, Mr. Behrman, a failed artist who lives downstairs. She implores him to paint a leaf on the wall outside Johnsy's window, hoping that it will provide the inspiration and hope her friend needs to fight against her illness. Mr. Behrman decides to paint one last masterpiece in order to give her hope. Despite his own failing health, he braves the harsh weather and paints a leaf on the wall, making it look like the last leaf on the tree. The next morning, Johnsy discovers that the last leaf has not fallen and her condition miraculously improves. Sue's relief and happiness is short lived as she discovers that Behrman has caught pneumonia and succumbs to it. Mr. Behrman's selfless act of painting the leaf not only saved Johnsy's life but also showed the girls the value of friendship and the strength to keep fighting even in the face of adversity. It was his final act of building ‘a bridge over troubled waters’. ‘The Last Leaf’, explores the themes of impending mortality, associated despair and the power of hope.The story emerges as an ode to life itself. It serves as a reminder that even in the face of adversity, a single act of kindness can change someone's life forever and there is always hope, even in the darkest of times.. It is also a testimony to the healing power of art. The painting eases Johnsy’s brooding preoccupations about death. Faith changes the course of our existence altogether. The flame of suffering can only be doused by a life affirming gutsy, breeze of kindness. As Henry James observed, “Three things in human life are important: the first is to be kind; the second is to be kind; and the third is to be kind.” “Please call me by my true names, so I can wake up, and so the door of my heart can be left open, the door of compassion”. Thich Nhat Hanh As we weave our lives in the vast tapestry of life, let us strive to embrace the power of kindness. Do pen your reflections here... Vaslav Nijisnsky was perhaps the greatest ballet dancer of all time. I first read about this talented artist,who was born on 12th March in 1889, in Colin Wilson’s book, ‘The Outsider’. It was a moving account of the extraordinary life and career of Nijinsky. He could perform en pointe with ease and his seemingly gravity-defying leaps were also legendary. Unfortunately he had a psychiatric breakdown when he was just 29 years old and died after battling with the illness for thirty years.

Nijinsky kept a meticulous account of his psychological travails in a diary which he wrote within a short span of six weeks. I read his poignant account when he was in the cusp of sanity and mental illness, in the Internet Archives. It was quite a difficult read and a revealing account of early stages of decline into a psychotic breakdown. For instance, in an accurate account of delusion of influence, he wrote “I write without thinking. I scratched my nose, thinking something was tickling me, but I realised that God did this on purpose so that I would correct my notebook. God writes all this for me”. I delved deeper into his mental illness through various sources. He was first taken to Eugene Bleuler at the Burgholzli. After examining him, Bleuler came out and told his wife Romola, “Now, my dear, be very brave. You have to take your child away; you have to get a divorce. Unfortunately, I am helpless. Your husband is incurably insane. I must seem to be brutal, but I have to be able to save you and your child – two lives. We physicians must try to save those whom we can; the others, unfortunately, we have to abandon to their cruel fate. I am an old man. I have sacrificed fifty years of my life to save them. I have searched and studied; I know the symptoms; I can diagnose it; but I don’t know. I wish I could help, but do not forget, my child, that sometimes miracles happen”. When Romola came out after the consultation, Nijisnsky’ response was “you are bringing me my death-warrant”. As he became quite symptomatic, he was forcibly taken to the Sanatorium Bellevue Kreuzlingen, where he was treated by Dr Binswanger. Romola took her husband to be examined by Jung and Sigmund Freud. Freud opined that psycho-analysis was useless in cases of schizophrenia. In spite of being taken care of by the giants in the history of psychiatry, he grew worse, continued to have hallucinations and was violent at times. Hoping for a miracle, Romola took him on a pilgrimage to Lourdes. “We spent several days there,” she wrote. “I went with Vaslav to the Grotto. I washed his forehead in the spring and prayed. I hoped and hoped, but he was not cured. Maybe my faith was not deep enough”. That year Romola heard about some new treatment approaches in schizophrenia and got in touch with Dr Sakel, who had invented insulin coma treatment. It was arranged that Sakel himself should administer the treatment. Bleuler, who saw him twenty years earlier, paid him a visit after 20 years and told Romola,”‘My dear Madame Nijinsky, many years ago I had the cruel task of informing you that, according to medical knowledge as it then was, your husband was incurably insane. I am happy today to be able to give you hope. This young colleague of mine has discovered a treatment for which I searched in vain for over forty years. I am proud of him. And of you, because you did not follow the advice I gave you so many years ago to divorce your husband. You stood by him during those years of mental dimness, you helped him through this terrible illness, and now I believe you will be rewarded. He will once more become himself.” The insulin shock had freed him from hallucinations and his restlessness abated significantly. Unfortunately Nijinsky never fully recovered from his illness.The Nazi regime gave orders to exterminate all psychiatric patients and he had to hide in a cave. After the war, he and Romola moved to London. He never saw any psychiatrist nor did he required admission during his time in the UK. He passed away on 8 April 1950 due to ‘uremia with chronic nephritis’. Most of the accounts about Nijinsky focus on his illness and the kind of treatment he received. What is missing in these narratives is the crucial role played by his wife Romona. Nijinsky was not an easy person to handle during his psychotic episodes and at times even became physical. Once during their walks in the mountain, Nijinsky suddenly pushed her and she narrowly missed falling into a precipice. She gathered herself, put her around him, remembering Bleuler’s advice that “one should never lose one’s nerve when a mental patient becomes agitated or violent; on the contrary, then one must show utter fearlessness.” She was constantly by his side, tending to him with affection, “Every afternoon I tried to interest Vaslav in small and simple matters, things which were related to his art, his youth or his hobbies. At first, it was an extremely thankless task. His tendency was to withdraw into himself…One had to draw his attention to something and then sustain it. It might be a rose in the garden, which I would show him and make him gather”. Nijinsky died in the presence of the woman who had been for thirty-seven years his wife, breadwinner, nurse and a second mother. In his final moments, he stretched out his right hand to Romona, who bent down and kissed it; “Thoughts and feelings were racing in my mind, but the enduring thought was: You were privileged among so many millions of women to share his life, to serve him. God gave him to you. He has taken him back.” Nijinsky’s illness career is a poignant reminder of the suffering associated with schizophrenia and the crucial role of caregivers in tending to those afflicted with it. To have someone who cares at the most difficult and challenging moments in life is truly a blessing. As Rollo May observed, “Care is a state in which something does matter; it is the source of human tenderness.” (I personally wish that lived experiences of people with mental illness and the narratives of caregivers find their rightful place in psychiatry textbooks). Feel free to pen your thoughts here... I had long standing desire to have a glimpse of the Brahmapureeswarar temple at Pullamangai, which was built during the reign of Parantaka I (907-954 CE), and is an outstanding example of early Chola temple architecture. During a visit to Trichy in connection with a wedding, I expressed my interest to my friend Dr T Krishnamurthy and one fine morning we set off to explore this place. Since it is often known as Brahmapureeswarar temple, guided by the google map, we landed in a place with a decrepit, dilapidated temple. We enquired around and were told that this was the Brahmapureeswarar temple. However, not convinced by this information, we went in search of the real one. Since Pasupathikoil is also mentioned in relation to the temple, we searched for and found an old temple which again was definitely not the one we were after. Fortunately, I found an old lady near the temple and I showed her the photo of the temple we wanted to visit. Without any hesitation, she described the precise direction to reach it, like a live google map and we finally landed up at Brahmapureeswarar temple at Pullamangai, only to find it locked up. It was a sleepy little village with a single road. TK went ahead, knocked at the doors of the houses and came back with the information that the priest in charge lived elsewhere and they did’nt have his contact number. Our spirits sank and it was also getting hotter. Noticing our plight, a few young boys on a bike, came up and said that they could guide us to the priest’s house. Energised by this information, TK climbed onto their bike and went in search of the priest. He came back triumphantly after a while, announcing that the priest had been located and he would come over shortly. It was music to our ears. A few minutes later, the priest arrived and opened the locks of the temple.

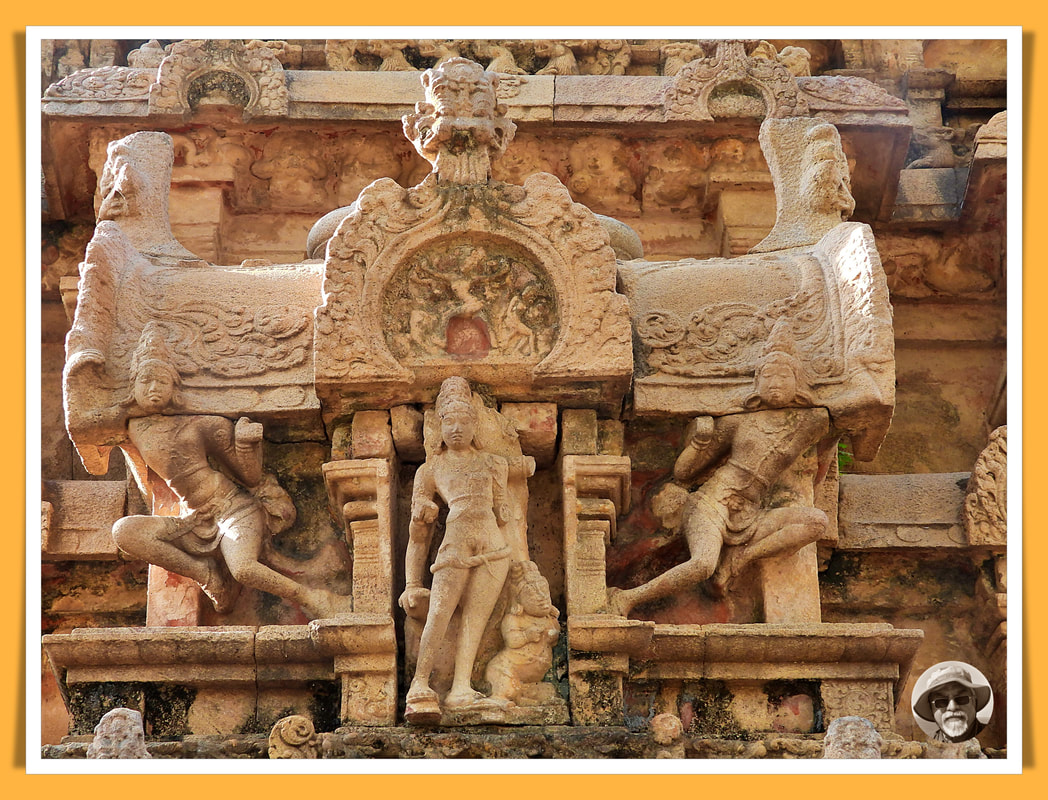

Brahmapureeswarar temple is a very small structure consisting of the main garbhagraha attached to an ardha mantapa, both of which were around six feet below ground. As a consequence the adhirstana is below the ground level. The first sculpture that took my breath away as I began circumambulating the temple was that of Ganesha. The god is seated on a throne with folded legs. His trunk hangs vertically and then curves to the left in the form of an inverted question mark. Ganesha is shielded by a beautifully sculpted parasol with a central pendant. Two saluting figures are shown in flying posture on either side. Ganesha, ‘Lord of the Ganas’, is flanked by joyous Ganas in three superimposed rows. One of them is holding Ganesha’s vahana (vehicle) Mushaka (Mouse). Right on top is the Makara Torana, with two Makaras carved on either side. Rows of Yalis, some of them with human riders, emerge from the mouth of the Makaras and form a canopy. Right in the middle of the canopy is a dancing figure (Siva?). Below it is another row of Ganas. In the midst of this elaborately carved canopy is a very small sculpture which depicts Siva, Parvati and Chandesa Nayanar. Incidentally,there is a large, beautifully carved sculpture of Chandesa Anugraha Murti in Gangaikondacholapuram. The Devakoshtas are adorned with beautiful sculptures. On the western wall there is Lingodhbhava flanked on either side by Brahma and Vishnu. There is an extraordinarily beautiful tall,long limbed, Brahma sculpture. According to ancient temple iconometry, sculptures are carved on the basis of the Tala system. Each Tala is equal to 12 Angulas. This particular sculpture of Brahma has been carved according to the Dasa (ten)tala system. On either side of Brahma are two Rishis writing down the Vedas chanted by him, on palm leafs. Curiously, in the midst of the makara torana on top was a small figure of Aalilai Kannan! There is also an interesting figure in the Vimana of Narasimha fondly holding Prahlada on his lap The niche on the northern wall of the temple is occupied by Durga with eight arms standing on the head of the buffalo. I was totally entranced by the sculpture and stood there for several minutes absorbing its beauty. Noticing my absorption, the priest moved aside the decorations adorning the idol, for me to have a good look. I have never seen a sculpture of Durga as stunning as the one in front of me. The goddess is tall and slender standing in a tribhanga pose: tri meaning “three” and bhanga meaning “posture”. It entails bending the body at three places, namely the knee, the hip and the shoulder. The flowing lines of the sculpture have an elegant, sinuous quality. Over her head is an umbrella (called the Venkotra Kudai). On the right above, is a small stylised lion and on the left a deer held by a bhuta. Two kneeling figures are depicted on the wall on either side of the main niche, cutting parts of their body as a sacrificial gesture. The person on the left is seen holding his hair with his left hand and is attempting to cut off his head with his right hand. The one on the right is about the cut off his leg at the knee. A similar depiction can be found in the Draupathi Ratham at Mahabalipuram. What struck me was the portrayal of Durga. Here the focus is not on the combat with Mahishasura but her triumphant visage after vanquishing him. There is sublime elegance in the depiction of Durga. Her face is very serene with a tranquil smile on her lips as described in the Devimahatmyam. ईषथ सहसं अमलं परिपूरण चन्द्र भीबनुकरी कनकोत्तमा कान्ति कण्ठम्. All the intricately carved, exceptionally proportioned,serene Devakoshta figures exude an air of nobility and gentleness. A distinctive feature of the temple is the rows of Yalis that have been carved on the base moldings. Each one is distinctive and the ones in the corner have warriors sculpted inside their wide open mouths. The adhirstana contains small sculptures 6 by 5 inches which depict various scenes from Puranas.Since these figures are six feet below the ground level, one has to get down to have a good look at them. Many of them have lost their sharpness and are in varying stages of decay. One possible reason may be that during the rainy season the moat surrounding them gets filled up with water and since there is no clear outlet for the water to drain, the stagnant water seeping into these small carvings must have eroded them. If this is not attended to, even the remaining ones will soon be lost, forever. One can also notice plants growing luxuriantly amidst the various sculptures in the vimana. There is an overwhelming sense of neglect pervading this little gem of a temple which is managed by the Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments Department of the Govt of Tamil Nadu. I wonder why it has not come under the purview of ASI, given its distinctive historical and aesthetic legacy. After we finished seeing the temple in detail we were talking with the priest and were shocked to hear that he was being paid a paltry sum of Rs.900 as a salary. With this meagre income, he carries on with his life officiating as a priest in religious functions. I was deeply moved by his plight but was also angry at the callous way these exceptional treasures are taken care of and managed by the state.e Do have a look at the glimpses of this beautiful temple at: drive.google.com/file/d/1vKLEQxckC-vn1adEXmOSoLwPI7UsL8Yw/view?usp=sharing Once you have had a good look, do pen your thoughts and reflections here! Each and every temple in India has an interesting story woven around it. For instance, the main idol in Thyagaraja temple at Thiruvarur is fully covered with flowers with only the face visible. Therein lies the fascinating story of Mucukunda, who is said to have brought the idol of Thyagaraja to the temple. I heard that a series of paintings dating back to 1660s narrate this episode in the Devasiriya mandapam in the temple precincts. Having a keen interest in the murals of this period, myself and Ahalya went over to Thiruvarur last month to catch a glimpse of them. Thanks to our dear friend Dr Chandrasekhar we were able to gain access to it.

Devasiriya mandapam was enveloped in darkness when we entered it and we were welcomed by hundreds of bats flying all around us. The floor was littered with layers of dust and bat droppings and the stench was quite overpowering. It was quite disheartening to see the condition of the place, which quickly gave way to one of sheer enchantment when we looked up at the ceiling. Each and every inch was painted in myriad colourful hues, recounting the mythical story of Mucukunda and how he brought the idol of Thyagarajaswamy to Thiruvarur. Legend has it that the idol of Thygaraja was resting on Vishnu’s chest in the cosmic ocean, moving in tandem with the Lord’s breath. When the demon Varkaliyan continuously troubled Indra, he sought Vishnu’s help. Vishnu handed him the idol of Thyagaraja and asked him to perform pooja to this idol to help him win the battle. With this, Indra was able to vanquish Varkaliyan. Later when another demon Vala bothered him, Vishnu told Indra to seek the help of the mythical Chola king, Mucukunda who had a monkey face. Thanks to Mucukunda’s help, Vala was trounced in a fearsome battel. A delighted Indra took Mucukunda to his abode and offered a boon to Mucukunda for helping him win the battle with the demon. Indra was stunned when Mucukunda asked for the idol of Thygaraja. He asked Vishwakarma to make 6 similar idols. The next day, Indra asked Mucukunda to pick any one of the 7 idols hoping that he would not be able to distinguish the real one. To his great surprise, Mucukunda was able to identify the original idol, which had a distinctive smiling expression. Delighted with his devotion, Indra handed him all the 7 idols. Mucukunda took the idol of Thygaraja and installed it in the sanctum of the temple at Thiruvarur. He then took the other 6 idols and installed them at Thiru Kolili, Thiru Kaaraayil, Thiru Maraikkadu, Thiru Vaaimoor, Thiru Nallaru and Thiru Nagai. Together, these are referred to as Saptha Vidanga Kshetrams. The word "Sapta" means "seven" in the local language, while "vidanga" means "not chiselled.’ The seven Siva Thalams with unchiseled bases were idols of the same image that Mucukunda had received from Indra. It is interesting to note that Ajapa Natanam, a special kind of dance without chanting (A-Japa: unuttered prayer) is enacted with swaying movements when the idol of Thygaraja is taken out in procession. As Vishnu held the idol of Thygaraja on his chest, these movements mimic the swaying of the idol with his breathing. It is performed with seven sacred steps which are believed to represent the seven chakras or energy centres in the human body. Each step is associated with a specific chakra and is said to activate and energize that particular chakra. Dating back to the late Nayaka/early Maratha period, these murals narrate this engaging story in several panels. A portion of these have been carefully restored by INTACH with support from Prakriti foundation. This entire process has been beautifully documented by VK Rajamani and David Shulman in a monograph. In spite of this important initiative to conserve these priceless murals, it was sad to see the state of the rest of them which are in varying stages of neglect. Seepage from the ceiling, bats and callous human neglect has taken a heavy toll on these precious treasures. I fail to understand why these beautiful murals are kept out of ‘public’ purview. No visitor can deface them since they are on the ceiling. The authorities can even charge an entry fee which can help in proper maintenance of the place. Right now there are more bats than visitors in the place! I photographed these murals (craning the neck up all the time!), in natural light, without flash, thanks to the light sensitive iPhone. I have collated these images in a pdf format and would strongly urge you to have a glimpse of these enchanting paintings. Do mail a request to [email protected] and I would send across the file! Once you have a look at them, come back to the blog and post your comments here! Victoria, the capital of Seychelles is a quaint little town, replete with enchanting colonial era buildings. It was a bright sunny morning and as we were walking along the city center, our guide pointed at a man who was attired in khaki shorts and shirts and whispered that he is Gérard Rocamora, the most famous ornithologist in Seychelles. I quickly walked up to him and introduced myself and shared my interest in watching some endemic birds of Seychelles. He was warm and friendly and enumerated some of the species that I would be able to see and even mimicked their calls and patterns of flight. I thanked him profusely and looked forward to seeing at least a few of the birds he had mentioned.

After spending sometime in the National Museum of History in Victoria, we made our way to the Seychelles Tea Factory. The winding road to the factory through evergreen towering trees was quite beautiful. Perched on the hills of Morne Blanc, the tea factory offered a splendid panoramic view of the western slopes of Mahé and its beaches. As I was soaking in the captivating landscape, I heard the calls of the Seychelles Blue Pigeon, which Dr Gerard Rocamora so wonderfully mimicked. On looking up, I spotted it on top of a tall tree. With a dark blue body, silver-grey breast and a striking patch of bright red skin on its face, the Seychelles Blue Pigeon has a regal appearance. It was first described by the Italian naturalist Giovanni Antonio Scopolli in 1786 and is known as 'Pizon Olande' ('Dutch Pigeon') in Creole. It derives its Creole name from the resemblance of its colors to the Dutch flag! Flutter of blue wings Etched in azure sky Zen moment |

Dr Raguram

Someone who keeps exploring beyond the boundaries of everyday life to savor and share those unforgettable moments.... Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed